In the spring of 1967 I spent several months in Nessakouya, a Melanesian village in the Houailou Valley on the east coast of New Caledonia.

Valley Landscape, oil on cardboard, 12”x11”, 1967

While teaching art to children at the Protestant mission school, I made paintings of my own along the nearby Houailou River. Araucaria pines marked the site of the ancestral village, displaced by French settlers.

Riverside Trees, oil on cardboard, 11”x15”, 1967

Studying modern French literature, Proust and Rimbaud, and the Albers color course had left me inspired by Cezanne and Klee.My work adopted the participatory approach of the children in my class, who I asked to depict the activities of the village. My landscapes are phenomenological rather than optical.

Path, oil on cardboard, 14”x11”, 1967

I painted this collapsing structure at the end of a side path after the chief’s wife spontaneously bought me a can of peas from the itinerant merchant who brought his truck up and down the valley. I took it as a sign of inclusion, and thought of this spot as “my place” in the village.

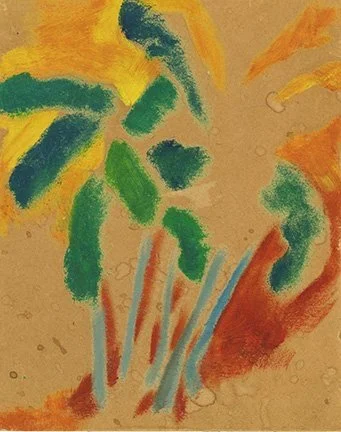

Banana, oil on cardboard, 14”x10”, 1967

William Carlos Williams speaks of the need for Americans to connect to the “local”, to places to which they have the deepest psychological connection. Through the children I felt I established a personal engagement with Nessakouya, a connection I’ve sought to re-establish with places I work in California. Schools have been an important connection to my local landscapes.